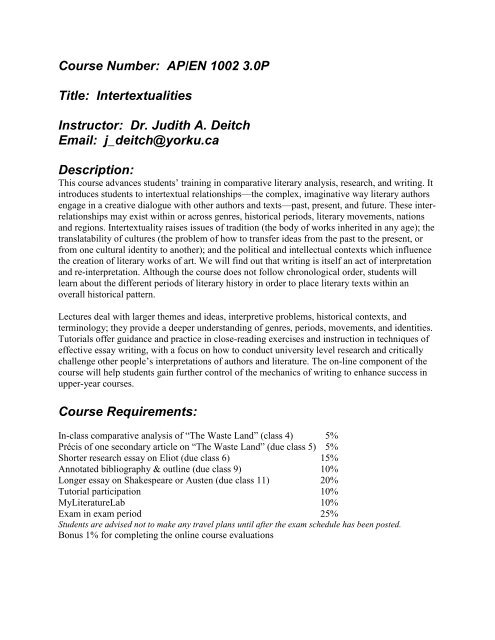

- Athol Fugard Picture

- The Island By Athol Fugard Pdf Free Printable

- The Coat By Athol Fugard

- The Island By Athol Fugard Pdf Free I Love

- The Island Athol Fugard

The play has four scenes. The Island is indeed an actor's play, for acting is its central metaphor and idea: acting as a means for the acting out of one's life, acting as a form of survival, and acting as a basis for (political) action. The Island is a play written by Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona. The Island By Athol Fugard Pdf Creator Posted on This article addresses the creation of Athol Fugard’s plays not as performances or as texts, but as material objects, and examines how the meaning and value of his plays were constructed through the interventions of his publisher. The Island is a play written by Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona. The apartheid-era drama, inspired by a true story, is set in an unnamed prison clearly based on South Africa's notorious Robben Island prison, where Nelson Mandela was held for twenty-seven years.

Athol Fugard Picture

The Island is a play written by Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona.

The apartheid-era drama, inspired by a true story, is set in an unnamed prison clearly based on South Africa's notorious Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was held for twenty-seven years. It focuses on two cellmates, one whose successful appeal means that his release draws near and one who must remain in prison for many years to come. They spend their days performing futile physical labor and nights rehearsing in their cell for a performance of Sophocles' Antigone in front of the other prisoners. One takes the part of Antigone, who defies the laws of the state to bury her brother, and the other takes the part of her uncle Creon, who sentences her to die for her crime of conscience. The play draws parallels between Antigone's situation and the situation of black political prisoners. Tensions arise as the performance approaches, especially when one of the prisoners learns that he has won an early release and the men's friendship is tested.

Structure[edit]

The play has four scenes. It opens with a lengthy mimed sequence in which John and Winston, two cell mates imprisoned on Robben Island, shovel sand in the scorching heat, dumping the sand at the feet of the other man, so that the pile of sand never diminishes. This is designed to exhaust the body and the morale of the prisoners. Later scenes include a play within a play, as Winston and John perform a condensed two-person version of Antigone by Sophocles.

History[edit]

The play was first performed in Cape Town, at a theatre called The Space, in July 1973. In order to evade the draconian censorship in South Africa at the time (plays dealing with prison conditions, etc., were prohibited), the play premiered under the title, Die Hodoshe Span. It was next staged at the Royal Court Theatre in London, with John Kani and Winston Ntshona portraying John and Winston respectively. The Broadway production, presented in repertory with Sizwe Banzi Is Dead, opened on November 24, 1974 at the Edison Theatre, where it ran for 52 performances.

In an unusual move, Kani and Ntshona were named co-Tony Award nominees (and eventual co-winners) for Best Actor in a Play for both The Island and Sizwe Banzi Is Dead.

Over the next thirty years, Kani and Ntshona periodically performed in productions of the play. Notable among them were the Royal National Theatre in 2000 [1], reported at the time as their final production, although they went on to star at the Old Vic in 2002 [2] and the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2004 [3].

Plot[edit]

John and Winston share a prison cell on an unnamed Island. After another day of hard labor and having been forced to run while shackled and then beaten, they return to their cell. They tend each other's wounds, share memories of times at the beach and rehearse for the prisoner-performed concert which is imminent. They are going to perform a scene from an abridged version of Antigone by Sophocles. John will play Creon and Winston will play Antigone.

When he sees himself in his costume, Winston tries to pull out of playing a female role, fearing he will be humiliated. John is called to the governor's office. He returns with news that his appeal was successful and his ten-year sentence has been commuted to three years: he will be free in three months. Winston is happy for him. As they imagine what leaving prison and returning home will be like, Winston begins to unravel. He doubts why he ever made a stand against the regime, why he even exists. Having said it, he experiences a catharsis, and accepts that he must endure.

The final scene is their performance of Antigone. After John-as-Creon sentences Winston-as-Antigone to be walled up in a cave for having defied him and done her duty towards her dead brother, Winston pulls off Antigone's wig and yells 'Gods of Our Fathers! My Land! My Home! Time waits no longer. I go now to my living death, because I honored those things to which honor belongs'. The final image is of John and Winston, chained together once more, running hard as the siren wails.

Characters[edit]

- John has been imprisoned for belonging to a banned organization.

- Winston, we find out later was imprisoned for burning his passbook in front of the police. This was a serious crime, as the passbook was used to segregate and control the South African people.

- Hodoshe, an unseen character: he is referred to and represented by the sound of a prison whistle. He is a symbol of the apartheid state and racist rule. The literal translation for Hodoshe is 'carrion fly' (as mentioned in the play), a large green fly.

Themes[edit]

- Obedience and civil disobedience

- Brotherhood

- Freedom – bodily freedom, freedom of conscience and freedom of the mind

- Memory, imagination, and the transformative power of performance

Language[edit]

Although the play is in English, Afrikaans and Xhosa words are spoken as well.

Broadway awards and nominations[edit]

- Tony Award for Best Play (co-nominee with Sizwe Banzi)

- Tony Award for Best Actor in Play (Kani and Ntshona, winners)

- Tony Award for Best Direction of a Play (nominee)

- Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Actor in a Play (Kani and Ntshona, co-nominees)

- Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Director of a Play (nominee)

- Drama Desk Award for Outstanding New Foreign Play (co-nominee with Sizwe Banzi)

External links[edit]

The Island By Athol Fugard Pdf Free Printable

| Born | Harold Athol Lannigan Fugard 11 June 1932 (age 86) Middelburg, Eastern Cape, South Africa |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Playwright, novelist, actor, director, teacher |

| Nationality | South African |

| Citizenship | South African and American |

| Education | UCT (dropped out) |

| Period | 1956–2019 |

| Genre | Drama, novel, memoir |

| Notable works | 'Master Harold'...and the Boys Blood Knot |

| Spouse | Sheila Meiring Fugard (m. 1956; div. 2015)Paula Fourie (m. 2016) |

| Children | Lisa |

Harold Athol Lanigan FugardOIS (born 11 June 1932) is a South African playwright, novelist, actor, and director who writes in South African English. He is best known for his political plays opposing the system of apartheid and for the 2005 Academy Award-winning film of his novel Tsotsi, directed by Gavin Hood.[1] Fugard was an adjunct professor of playwriting, acting and directing in the Department of Theatre and Dance at the University of California, San Diego.[2] For the academic year 2000–2001, he was the IU Class of 1963 Wells Scholar Professor at Indiana University, in Bloomington, Indiana.[3] He is the recipient of many awards, honours, and honorary degrees, including the 2005 Order of Ikhamanga in Silver 'for his excellent contribution and achievements in the theatre' from the government of South Africa.[4] He is also an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.[5]

- 2Career

Personal history[edit]

Fugard was born as Harold Athol Lanigan Fugard, in Middelburg, Eastern Cape, South Africa, on 11 June 1932. His mother, Marrie (Potgieter), an Afrikaner, operated first a general store and then a lodging house; his father, Harold Fugard, was a disabled former jazz pianist of Irish, English and French Huguenot descent.[1][6][7] In 1935, his family moved to Port Elizabeth.[8] In 1938, he began attending primary school at Marist Brothers College.[9] After being awarded a scholarship, he enrolled at a local technical college for secondary education and then studied Philosophy and Social Anthropology at the University of Cape Town,[10] but he dropped out of the university in 1953, a few months before final examinations.[1] He left home, hitchhiked to North Africa with a friend, and then spent the next two years working in east Asia on a steamer ship, the SS Graigaur,[1] where he began writing, an experience 'celebrated' in his 1999 autobiographical play The Captain's Tiger: a memoir for the stage.[11]

In September 1956, he married Sheila Meiring, a University of Cape Town Drama School student whom he had met the previous year.[1][12] Now known as Sheila Fugard, she is a novelist and poet. The couple have since divorced. Their daughter, Lisa Fugard, is also a novelist.[13]

The Fugards moved to Johannesburg in 1958, where he worked as a clerk in a Native Commissioners' Court, which 'made him keenly aware of the injustices of apartheid.'[1] He was good friends with prominent local anti-apartheid figures, which had a profound impact on Fugard, whose plays' political impetus brought him into conflict with the national government; to avoid prosecution, he had his plays produced and published outside South Africa.[12][14] A former alcoholic, Athol Fugard has been teetotal since the early 1980s.[15]

For several years Fugard lived in San Diego, California,[16] where he taught as an adjunct professor of playwriting, acting, and directing in the Department of Theatre and Dance at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD).[2][14] In 2012, Fugard relocated to South Africa, where he now lives permanently.[17][18] In 2016, in New York City Hall, Fugard was married to South African writer and academic Paula Fourie.[19] Fugard and Fourie presently live in the Cape Winelands region of South Africa.

Career[edit]

Early period[edit]

In 1958, Fugard organised 'a multiracial theatre for which he wrote, directed, and acted', writing and producing several plays for it, including No-Good Friday (1958) and Nongogo (1959), in which he and his colleague black South African actor Zakes Mokae performed.[1]

After returning to Port Elizabeth in the early 1960s, Athol and Sheila Fugard started The Circle Players,[1] which derives its name from their production of The Caucasian Chalk Circle, by Bertolt Brecht.[20]

In 1961, in Johannesburg, Fugard and Mokae starred as the brothers Morris and Zachariah in the single-performance world première of Fugard's play The Blood Knot (revised and retitled Blood Knot in 1987), directed by Barney Simon.[21]

In 1962, Fugard publicly supported the Anti-Apartheid Movement (1959–94), an international boycott of South African theatres due to their segregated audiences, leading to government restrictions on him and police surveillance of him and his theatre, and leading him to have his plays published and produced outside South Africa.[14]

Lucille Lortel produced The Blood Knot at the Cricket Theatre, Off Broadway, in New York City, in 1964, 'launch[ing]' Fugard's 'American career.'[22]

The Serpent Players[edit]

In the 1960s, Fugard formed the Serpent Players, whose name derives from their first venue, the former snake pit (hence the name) at the Port Elizabeth Museum,[14] 'a group of black actors worker-players who earned their living as teachers, clerks, and industrial workers, and cannot thus be considered amateurs in the manner of leisured whites', developing and performing plays 'under surveillance of the Security Police according to Loren Kruger's The Dis-illusion of Apartheid published in 2004.'[23] The group largely consisted of black men, including Winston Ntshona, John Kani, Welcome Duru, Fats Bookholane and Mike Ngxolo as well as Nomhle Nkonyeni and Mabel Magada. They all got together, albeit at different intervals, and decided to do something about their lives using the stage. In 1961 they met Athol Fugard, a white man who grew up in Port Elizabeth and who recently returned from Johannesburg, and asked him if he could work with them as he had the theatre know-how, how to use the stage, movements, and everything else.[24] They worked with Athol Fugard since then and that is how the Serpent Players go together. At the time, the group performed anything they could lay their hands on in South Africa as they had no access to any libraries. These included Bertolt Brecht, August Strindberg, Samuel Beckett, William Shakespeare and many other prominent playwrights of the time. In an interview in California, Ntshona and Kani were asked why they were doing the play Sizwe Banzi is Dead, which was considered a highly political and telling story of the South African political landscape at the time. Ntshona answered: “We are just a group of artists who love theatre. And we have every right to open the doors to anyone who wants to take a look at our play and our work. We believe that art is life and conversely, life is art. And no sensible man can divorce one from the other. That’s it. Other attributes are merely labels”. They mainly performed at the St Stephen's Hall - renamed the Douglas Ngange Mbopa Memorial Hall in 2013 - adjacent to St Stephen's Church, and other spaces in and around New Brighton, the oldest Black township in Port Elizabeth.

According to Loren Kruger, Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Chicago,

the Serpent Players used Brecht's elucidation of gestic acting, dis-illusion, and social critique, as well as their own experience of the satiric comic routines of urban African vaudeville, to explore the theatrical force of Brecht's techniques, as well as the immediate political relevance of a play about land distribution. Their work on the Caucasian Chalk Circle and, a year later, on Antigone[14] led directly to the creation, in 1966, of what is still [2004] South Africa's most distinctive Lehrstück [learning play]:'The Coat. Based on an incident at one of the many political trials involving the Serpent Players, The Coat dramatized the choices facing a woman whose husband, convicted of anti-apartheid political activity, left her only a coat and instructions to use it.[23]

The Serpent Players conceptualised and co-authored many plays that they subsequently went on to perform for a variety of audiences in many theatres around the world. The following are some of their notable and most popular plays:

- Their first production was Niccolo Machiavelli’s La Mandragola, directed by Fugard as The Cure and set in the township. Other productions include Georg Buchner’s Woyzeck, Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle and Sophocle’s Antigone. When the group had turned to improvisation, they came up with classic works such as Sizwe Banzi is Dead and The Island, emerging as inner experiences of the actors who are also the co-authors of the plays.

- In The Coat, Kruger observes, 'The participants were engaged not only in representing social relationships on stage but also on enacting and revising their own dealings with each other and with institutions of apartheid oppression from the law courts downward', and 'this engagement testified to the real power of Brecht's apparently utopian plan to abolish the separation of player and audience and to make of each player a 'statesman' or social actor.... Work on The Coat led indirectly to the Serpent Players' most famous and most Brechtian productions, Sizwe Bansi is Dead (1972) and The Island (1973).'[23]

Fugard developed these two plays for the Serpent Players in workshops, working with John Kani and Winston Ntshona,[23] publishing them in 1974 with his own play Statements After an Arrest Under the Immorality Act (1972). The authorities considered the title of The Island, which alludes to Robben Island, the prison where Nelson Mandela was being held, too controversial, so Fugard and the Serpent Players used the alternative title The Hodoshe Span (Hodoshe meaning 'carrion fly' in Xhosa).Template:'Wertheim215'

- These plays 'espoused a Brechtian attention to the demonstration of gest and social situations and encouraged audiences to analyze rather than merely applaud the action'; for example, Sizwe Banzi Is Dead, which infused a Brechtian critique and vaudevillian irony-–especially in Kani's virtuoso improvisation-–even provoked an African audience's critical interruption and interrogation of the action.[23]

- While dramatising frustrations in the lives of his audience members, the plays simultaneously drew them into the action and attempted to have them analyse the situations of the characters in Brechtian fashion, according to Kruger.[23]

- Blood Knot was filmed by BBC Television in 1967, with Fugard's collaboration, starring the Jamaican actor Charles Hyatt as Zachariah and Fugard himself as Morris, as in the original 1961 première in Johannesburg.[25] Less pleased than Fugard, the South African government of B. J. Vorster confiscated Fugard's passport.[6][26]

Later period[edit]

'Master Harold'...and the Boys, written in 1982, incorporates 'strong autobiographical matter'; nonetheless 'it is fiction, not memoir', as Cousins: A Memoir and some of Fugard's other works are subtitled.[27]

His post-apartheid plays, such as Valley Song, The Captain's Tiger: a memoir for the stage and his 2007 play, Victory, focus more on personal than political issues.[28][29]

The Fugard Theatre, in the District Six area of Cape Town opened with performances by the Isango Portobello theatre company in February 2010 and a new play written and directed by Athol Fugard, The Train Driver, played at the theatre in March 2010.[30]

Fugard's plays are produced internationally, have won multiple awards, and several have been made into films, including among their actors Fugard himself.[31]

His film debut as a director occurred in 1992, when he co-directed the adaptation of his play The Road to Mecca with Peter Goldsmid, who also wrote the screenplay.[31]

The film adaptation of his novel Tsotsi, written and directed by Gavin Hood, won the 2005 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 2006.[31]

Plays[edit]

In chronological order of first production and/or publication:[6][32][33][34][35]

|

|

Bibliography[edit]

- Statements: [Three Plays]. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press (OUP), 1974. ISBN0-19-211385-2 (10). ISBN978-0-19-211385-6 (13). ISBN0-19-281170-3 (10). ISBN978-0-19-281170-7 (13). (Co-authored with John Kani and Winston Ntshona; see below.)

- Three Port Elizabeth Plays: Blood Knot; Hello and Goodbye; andBoesman and Lena. Oxford and New York, 1974. ISBN0-19-211366-6.

- Sizwe Bansi Is Dead and The Island. New York: Viking Press, 1976. ISBN0-670-64784-5

- Dimetos and Two Early Plays. Oxford and New York: OUP, 1977. ISBN0-19-211390-9.

- Boesman and Lenaand Other Plays. Oxford and New York: OUP, 1980. ISBN0-19-570197-6.

- Selected Plays of Fugard: Notes. Ed. Dennis Walder. London: Longman, 1980. Beirut: York Press, 1980. ISBN0-582-78129-9.

- Tsotsi: a novel. New York: Random House, 1980. ISBN978-0-394-51384-3.

- A Lesson from Aloes: A Play. Oxford and New York: OUP, 1981.

- Marigolds in August. A. D. Donker, 1982. ISBN0-86852-008-X.

- Boesman and Lena. Oxford and New York: OUP, 1983. ISBN0-19-570331-6.

- People Are Living There. Oxford and New York: OUP, 1983. ISBN0-19-570332-4.

- 'Master Harold'...and the Boys. New York and London: Penguin, 1984. ISBN0-14-048187-7.

- The Road to Mecca: A Play in Two Acts. London: Faber and Faber, 1985. ISBN0-571-13691-5. [Suggested by the life and work of Helen Martins of New Bethesda, Eastern Cape, South Africa.]

- Selected Plays. Oxford and New York: OUP, 1987. ISBN0-19-281929-1. [Includes: 'Master Harold'...and the Boys; Blood Knot (new version); Hello and Goodbye; Boesman and Lena.]

- A Place with the Pigs: a personal parable. London: Faber and Faber, 1988. ISBN0-571-15114-0.

- My Children! My Africa! and Selected Shorter Plays. Ed. and introd. Stephen Gray. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand UP, 1990. ISBN1-86814-117-9.

- Blood Knot and Other Plays. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 1991. ISBN1-55936-019-4.

- Playland and Other Worlds. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand UP, 1992. ISBN1-86814-219-1.

- The Township Plays. Ed. and introd. Dennis Walder. Oxford and New York: OxfordUP, 1993. ISBN0-19-282925-4 (10). ISBN978-0-19-282925-2 (13). [Includes: No-good Friday, Nongogo, The Coat, Sizwe Bansi Is Dead, and The Island.]

- Cousins: A Memoir, Johannesburg: Witwatersrand UP, 1994. ISBN1-86814-278-7.

- Hello and Goodbye. Oxford and New York: OUP, 1994. ISBN0-19-571099-1.

- Valley Song. London: Faber and Faber, 1996. ISBN0-571-17908-8.

- The Captain's Tiger: A Memoir for the Stage. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand UP, 1997. ISBN1-86814-324-4.

- Athol Fugard: Plays. London: Faber and Faber, 1998. ISBN0-571-19093-6.

- Interior Plays. Oxford and New York: OUP, 2000. ISBN0-19-288035-7.

- Port Elizabeth Plays. Oxford and New York: OUP, 2000. ISBN0-19-282529-1.

- Sorrows and Rejoicings. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 2002. ISBN1-55936-208-1.

- Exits and Entrances. New York: Dramatists Play Service, 2004. ISBN0-8222-2041-5.

- Co-authored with John Kani and Winston Ntshona

- Statements: [Three Plays]. 1974. By Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona. Rev. ed. Oxford and New York: OUP, 1978. ISBN0-19-281170-3 (10). ISBN978-0-19-281170-7 (13). ['Two workshop productions devised by Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona, and a new play'; includes: Sizwe Bansi Is Dead and The Island, and Statements After an Arrest Under the Immorality Act.]

- Co-authored with Ross Devenish

- The Guest: an episode in the life of Eugene Marais. By Athol Fugard and Ross Devenish. Craighall: A. D. Donker, 1977. ISBN0-949937-36-3. (Die besoeker: 'n episode in die lewe van Eugene Marais. Trans. into Afrikaans by Wilma Stockenstrom. Craighall: A. D. Donker, 1977. ISBN0-949937-43-6.)

Filmography[edit]

- Films adapted from Fugard's plays and novel[31]

- Boesman and Lena (1974), dir. Ross Devenish

- Marigolds in August (1980), dir. Ross Devenish

- 'Master Harold'...and the Boys (1984), Television movie, dir. Michael Lindsay-Hogg, first broadcast on Showtime[36]

- The Road to Mecca (1991), co-dir. by Fugard and Peter Goldsmid (screen adapt.)

- Boesman and Lena (2000), dir. John Berry

- Tsotsi (2005), screen adapt. and dir. Gavin Hood; 2005 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film[1]

- 'Master Harold'...and the Boys' (2010), dir. Lonny Price

- Film roles[31]

- Boesman and Lena (1974) - Boesman

- The Guest at Steenkampskraal (1977)[37] - Eugene Marais

- Meetings with Remarkable Men (1979)[38] - Professor Skridlov

- Marigolds in August (1980) - Paulus Olifant

- Gandhi (1982) - General Jan Smuts

- The Killing Fields (1984) - Doctor Sundesval

- The Road to Mecca (1991) - The Reverend Marius Byleveld

Selected awards and nominations[edit]

- Praemium Imperiale 2014[39]

- Theatre[40]

- Obie Award

- 1971 – Best Foreign Play – Boesman and Lena (winner)[41]

- Tony Award

- 1975 – Best Play – Sizwe Banzi Is Dead / The Island – Athol Fugard, John Kani and Winston Ntshona (nomination)

- 2011 – Special Tony Award Lifetime Achievement in the Theatre (winner)

- New York Drama Critics' Circle Awards

- 1981 – Best Play – A Lesson From Aloes (winner)

- 1988 – Best Foreign Play – The Road to Mecca (winner)[41]

- Evening Standard Award

- 1983 – Best Play – 'Master Harold'...and the Boys (winner)

- Drama Desk Awards

- 1982 – 'Master Harold'...and the Boys (winner)

- Lucille Lortel Awards

- 1992 – Outstanding Revival – Boesman and Lena (winner)[41]

- 1996 – Outstanding Body of Work (winner)[42]

- The Audie Awards (Audio Publishers Association)

- 1999 – Theatrical Productions – The Road to Mecca (winner)[43]

- Outer Critics Circle Award

- 2007 – Outstanding New Off-Broadway Play – Exits and Entrances (nomination)[41]

- Honorary awards

- Writers Guild of America, East Award

- 1986 – Evelyn F. Burkey Memorial Award – (along with Lloyd Richards)

- National Orders Award (South Africa)

- 2005 – The Order of Ikhamanga in Silver – 'for his excellent contribution and achievements in the theatre'[4]

- American Academy of Achievement's Golden Plate Award [44]

- 2014 - Golden Plate Award

- Honorary degrees

- Yale University, 1983[45]

- Wittenberg University, 1992[46]

- University of the Witwatersrand, 1993[47]

- Brown University, 1995[48]

- Princeton University, 1998[49]

- University of Stellenbosch, 2006[50]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ abcdefghiCraig McLuckie (Okanagan College) (3 October 2003). 'Athol Fugard (1932–)'. The Literary Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 25 August 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2008.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ ab'Athol Fugard'. University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ^Athol Fugard and Bruce Burgun (IUB theater professor) (29 September 2000). 'Conversation On line with South African Dramatist Athol Fugard'. Indiana University at Bloomington. Archived from the original on 11 September 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2008.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link) (RealAudio clip of interview.)

- ^ ab'Harold Athol Lanigan Fugard (1932 -)'. 2005 National Orders Awards. South African Government Online (info.gov.za). 27 September 2005. Archived from the original(Web) on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^'Fellows'. Royal Society of Literature. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^ abcIain Fisher. 'Athol Fugard: Biography'. Athol Fugard: Statements. iainfisher.com. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ^Fisher gives Fugard's full birth name as 'Harold Athol Lanigan Fugard', spelling Fugard's middle name as Lanigan, following Dennis Walder, Athol Fugard, Writers and Their Work (Tavistock: Northcote House in association with the British Council, 2003). It is spelled as Lannigan in Athol Fugard, Notebooks 1960–1977 (New York: Theatre Communications Group, 2004) and in Stephen Gray's Athol Fugard (Johannesburg and New York: McGraw-Hill, 1982) and many other publications. The former spelling (single n) seems more authoritative, however, as it is also used by Marianne McDonald, a close UCSD colleague and friend of Fugard, in 'A Gift for His Seventieth Birthday: Athol Fugard's Sorrows and Rejoicings'Archived 24 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Department of Theatre and Dance, University of California, San Diego, rpt. from TheatreForum 21 (Summer/Fall 2002); in Fugard's National Orders Award (27 September 2005) from the government of South Africa, presented to 'Harold Athol Lanigan Fugard (1932 –)'; and in his 'Full Profile' in Who's Who of Southern Africa (2007).

- ^Athol Fugard; Dennis Walder, ed. and introd (2000). The Township Plays. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. pp. M1 xvi. ISBN978-0-19-282925-2.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link) (Google Books limited preview.)

- ^'History: St Dominic's Prior School ... Marist Brothers College'(Web). St Dominic's Priory School. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^'Boesman and Lena – Author Biography'. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^Albert Wertheim (2000). The Dramatic Art of Athol Fugard: From South Africa to the World. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2000. pp. M1 215, M1 224–38. ISBN978-0-253-33823-5. (Google Books limited preview.)

- ^ abSheila Fugard. 'The Apprenticeship Years: Athol Fugard issue'. Twentieth Century Literature. findarticles.com. 39.4 (Winter 1993). Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^Alden Mudge (1 January 2006). 'African Odyssey: Lisa Fugard Explores the Moral Ambiguities of Apartheid'. First Person: Interview. Bookpage.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ^ abcdeMarianne McDonald (Professor of Theatre and Classics) (April 2003). 'Introd. of Athol Fugard'(YouTubeVideo clip). Times Topics, The New York Times. Retrieved 1 October 2008.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link) [Times Topics menu includes link to UCSD YouTube clip of Athol Fugard's lecture, 'A Catholic Antigone: an episode in the life of Hildegard of Bingen', Eugene M. Burke C.S.P. Lectureship on Religion and Society, University of California, San Diego (UCSD).]

- ^Athol Fugard (31 October 2010). 'Once upon a life: Athol Fugard'. The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 November 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^Athol Fugard & Serena Davies (8 April 2007). 'My Week: Athol Fugard'. Telegraph.co.uk. London. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^'Athol Fugard Gets Personal In 'Shadow of the Hummingbird' At Long Wharf'. Hartford Courant. 23 March 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^Samodien, Leila (17 July 2014). 'Athol Fugard wins prestigious award'. Cape Times. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^2, Creative Feel (13 May 2016). 'Congratulations Athol Fugard & Paula Fourie Creative Feel'. Creative Feel. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^Loren Kruger (2004). 'Chapter 5: The Dis-illusion of Apartheid: Brecht in South Africa'. Post-Imperial Brecht Politics and Performance, East and South. Cambridge Studies in Modern Theatre. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge UP, 2004. pp. M1 215–80. ISBN978-0-521-81708-0. (Google Books.)

- ^Mel Gussow (24 September 1985). 'Stage: 'The Blood Knot' by Fugard'. The New York Times. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^'Athol Fugard: Biography'. The Internet Off-Broadway Database. Archived from the original on 15 March 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ^ abcdefLoren Kruger (2004). 'Chapter 5: The Dis-illusion of Apartheid: Brecht in South Africa'. Post-Imperial Brecht Politics and Performance, East and South. Cambridge Studies in Modern Theatre. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge UP, 2004. pp. M1 217–18. ISBN978-0-521-81708-0. (Google Books limited preview.)

- ^Art is Life and Life is Art (1976) An interview with John Kani and Winston Ntshona of the Serpent Players of South Africa in Ufahamu: a journal of African Studies [Internet], 6(2), pp. 5 – 26. Available from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/9qb6w2wz [Accessed 26 July 2017]

- ^Athol Fugard (1983). Notebooks 1960–1977. Craighall: A. D. Donker, 1983. ISBN0-86852-011-X.

Back in S'Kop after five weeks in London for BBC TV production of The Blood Knot. Myself as Morrie, with Charles Hyatt as Zach. Robin Midgley directing. Midgley reduced the play to 90 minutes....Midgley did manage to dig up things that had been missed in all the other productions. Most exciting was his treatment of the letter writing scene – 'Address her' – which he turned into an essay in literacy...Zach sweating as the words clot in his mouth....

- ^Dennis Walder, 'Crossing Boundaries: The Genesis of the Township Plays', Special issue on Athol Fugard, Twentieth Century Literature (Winter 1993); rpt. findarticles.com. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^Albert Wertheim (2000). The Dramatic Art of Athol Fugard: From South Africa to the World. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2000. pp. M1 225. ISBN978-0-253-33823-5. (Google Books limited preview.)

- ^Brian Logan (28 July 2007). 'Finally, It's Personal'. The Times. London. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

[Fugard's] plays helped to end apartheid, but it's Athol Fugard's own life that now inspires his work.

- ^Charles Spencer (17 August 2007). 'Victory: The Fight's Gone Out of Fugard'. The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 1 October 2008. [Theatre review of Victory at the Theatre Royal, Bath.]

- ^Dugger, Celia W. (13 March 2010). 'His Next Act: Driving Out Apartheid's Ghost'. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ abcde'Filmography' in Athol Fugard at AllMovie. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ^Iain Fisher. 'Athol Fugard: Plays'(Web). Athol Fugard: Statements. iainfisher.com. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

Some of his plays are grouped together. Sometimes this is based on the subject matter (the Port Elizabeth plays), sometimes it is based on a period and style (the Statement Plays). ... But no category is complete, and there is overlap (The Township and The Statement Plays) and some plays do not easily fit into any categories.

- ^Fisher observes in the Fugard 'Biography' section of Athol Fugard: Statements that South African writer and critic Stephen Gray classifies many of Fugard's dramatic works according to chronological periods of composition and similarities of style: 'Apprenticeship' ([1956–]1957); 'Social Realism' (1958–1961); 'Chamber Theatre' (1961–1970); 'Improvised Theatre' (1966–1973); and 'Poetic Symbolism' (1975[–1990]).

- ^Stephen Gray, ed. (1991). File on Fugard. London: Methuen Drama, 1991. ISBN978-0-413-64580-7.

- ^Athol Fugard; Stephen Gray, ed. and introd (1990). My Children! My Africa! and Selected Shorter Plays. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand UP, 1990. ISBN1-86814-117-9.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

- ^Master Harold...and the Boys at AllMovie. Accessed 3 October 2008.

- ^The Guest at Steenkampskraal at AllMovie. Accessed 4 October 2008.

- ^Meetings with Remarkable Men at AllMovie. Accessed 3 October 2008.

- ^'STIAS Fellow Athol Fugard receives prestigious 2014 prize'. Stellenbosch University. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^A list of Fugard's Broadway theatre award nominations may be found at the IBDB. 'Athol Fugard: Awards'. Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on 4 March 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ^ abcd'Athol Fugard: Award Nominations; Award(s) Won'. The Internet Off-Broadway Database. Archived from the original on 15 March 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ^'Lucille Lortel Awards Archive: 1986–2000'. Lortel Archives. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ^'The Audie Awards: 1999'(Web). Writers Write, Inc. Retrieved 2 October 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^'Athol Fugard Biography and Interview'. www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^'Yale University: Honorary Degree Honorands: 1977–2000'(PDF). Yale University. Archived from the original(PDF) on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^'Honorary Degree Recipients: 1948–2001'. Wittenberg University. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^'Honorary Graduates: 1920s to 2000s'(Web). University of the Witwatersrand. Archived from the original on 3 August 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^'News release 94–185'(Web) (Press release). Brown University News Bureau (Sweeney). 24 May 1995. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^'Honorary Degrees Awarded by Princeton University: 1940s to 2000s'(Web). Princeton University. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^Zeninjor Enwemeka (21 April 2006). 'Stellenbosch honours Athol Fugard'. IOL. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

References[edit]

- The Amajuba Resource Pack. The Oxford Playhouse and Farber Foundry: In Association with Mmabana Arts Foundation. Oxford Playhouse, October 2004. Accessed 1 October 2008. Downloadable PDF. ['Photographs by Robert Day; Written by Rachel G. Briscoe; Edited by Rupert Rowbotham; Overseen by Yael Farber.' 18 pages.]

- Athol Fugard. Special issue of Twentieth Century Literature 39.4 (Winter 1993). Index. Findarticles.com. <http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0403/is_n4_v39>. Accessed 4 October 2008. [Includes: Athol Fugard, 'Some Problems of a Playwright from South Africa' (Transcript. 11 pages).]

- Blumberg, Marcia Shirley, and Dennis Walder, eds. South African Theatre As/and Intervention. Amsterdam and Atlanta, Georgia: Editions Rodopi B.V., 1999. ISBN90-420-0537-8 (10). ISBN978-90-420-0537-2 (13).

- Fugard, Athol. A Lesson from Aloes. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 1989. ISBN1-55936-001-1 (10). ISBN978-1-55936-001-2 (13). Google Books. Accessed 1 October 2008. (Limited preview available.)

- –––, and Chris Boyd. 'Athol Fugard on Tsotsi, Truth and Reconciliation, Camus, Pascal and 'courageous pessimism'....'The Morning After: Performing Arts in Australia (Blog). WordPress. 29 January 2006. Accessed 4 October 2008. ['An edited interview with South African playwright Athol Fugard (in San Diego) on the publication of his only novel Tsotsi in Australia, 29 January 2006.']

- –––, and Serena Davies. 'My Week: Athol Fugard'. The Telegraph 8 April 2007. Accessed 29 September 2008. [The playwright describes his week to Serena Davies, prior to the opening of his play Victory at the Theatre Royal, Bath (telephone interview).]

- Gray, Stephen. Athol Fugard. Johannesburg and New York: McGraw-Hill, 1982. ISBN0-07-450633-1 (10). ISBN978-0-07-450633-2 (13). ISBN0-07-450615-3 (10). ISBN978-0-07-450615-8 (13).

- –––, ed. and introd. File on Fugard. London: Methuen Drama, 1991. ISBN0-413-64580-0 (10). ISBN978-0-413-64580-7 (13).

- –––. My Children! My Africa! and Selected Shorter Plays, by Athol Fugard. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand UP, 1990. ISBN1-86814-117-9.

- Kruger, Loren. Post-Imperial Brecht Politics and Performance, East and South. Cambridge Studies in Modern Theatre. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge UP, 2004. ISBN0-521-81708-0 (10). ISBN978-0-521-81708-0 (13). (Google Books; limited preview available.)

- McDonald, Marianne. 'A Gift for His Seventieth Birthday: Athol Fugard's Sorrows and Rejoicings'. Department of Theatre and Dance. University of California, San Diego. Rpt. from TheatreForum 21 (Summer/Fall 2002). Accessed 2 October 2008.

- McLuckie, Craig (Okanagan College). 'Athol Fugard (1932–)'. The Literary Encyclopedia. 8 October 2003. Accessed 29 September 2008.

- Morris, Stephen Leigh. 'Falling Sky: Athol Fugard's Victory'. LA Weekly 31 January 2008. Accessed 29 September 2008. (Theatre review of the American première at The Fountain Theatre, Los Angeles, California.)

- Spencer, Charles. 'Victory: The Fight's Gone Out of Fugard'. The Telegraph 17 August 2007. Accessed 30 September 2008. [Theatre review of Victory at the Theatre Royal, Bath.]

- Walder, Dennis. Athol Fugard. Writers and Their Work. Tavistock: Northcote House in association with the British Council, 2003. ISBN0-7463-0948-1 (10). ISBN978-0-7463-0948-3 (13).

- Wertheim, Albert. The Dramatic Art of Athol Fugard: From South Africa to the World. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2000. ISBN0-253-33823-9 (10). ISBN978-0-253-33823-5 (13).

- –––, ed. and introd. Athol Fugard: A Casebook. [Casebooks on Modern Dramatists]. Gen. Ed., Kimball King. New York: Garland Publishing, 1997. ISBN0-8153-0745-4 (10). ISBN978-0-8153-0745-7 (13). (Out of print; unavailable.) [Hardcover ed. published by Garland Publishing; the series of Casebooks on Modern Dramatists is now published by Routledge, an imprint of Taylor & Francis, and does not include this title.]

External links[edit]

- 'Athol Fugard'. Faculty profile. Department of Theatre and Dance. University of California, San Diego. (Lists Athol Fugard: Statements: An Athol Fugard site by Iain Fisher as 'Personal Website'; see below.)

- Athol Fugard at AllMovie

- Athol Fugard at the Internet Broadway Database

- Athol Fugard on IMDb

- Athol Fugard at the Internet Off-Broadway Database (IOBDb)

- Athol Fugard at Times Topics in The New York Times. (Includes YouTubeVideo clip of Athol Fugard's Burke Lecture 'A Catholic Antigone: An Episode in the Life of Hildegard of Bingen', the Eugene M. Burke C.S.P. Lectureship on Religion and Society, at the University of California, San Diego, introduced by Professor of Theatre and Classics Marianne McDonald, UCSD Department of Theatre and Dance, April 2003 [Show ID: 7118]. 1:28:57 [duration].)

- Athol Fugard at WorldCat

- 'Athol Fugard Biography' – 'Athol Fugard', rpt. by bookrags.com (Ambassadors Group, Inc.) from the Encyclopedia of World Biography. ('2005–2006 Thomson Gale, a part of the Thomson Corporation. All rights reserved.')

- 'Athol Fugard (1932– )' at Britannica Online Encyclopedia (subscription based; free trial available)

- 'Athol Fugard (1932– )' – Complete Guide to Playwright and Plays at Doollee.com

- Athol Fugard: Statements: An Athol Fugard site by Iain Fisher. (Listed as 'Personal Website' in UCSB faculty profile; see above.)

- 'Books by Athol Fugard' at Google Books (several with limited previews available)

- 'Full Profile: Mr Athol 'Lanigan' Fugard' in Who's Who of Southern Africa. Copyright 2007 24.com (Media24). (Includes hyperlinked 'News Articles' from 2000 to 2008.)

- 'Interviews: South Africa's Fugards: Writing About Wrongs'. Morning Edition. National Public Radio. NPR RealAudio. 16 June 2006. (With hyperlinked 'Related NPR stories' from 2001 to 2006.)

- Lloyd Richards (Summer 1989). 'Athol Fugard, The Art of Theater No. 8'. Paris Review.

- 'Athol Fugard' in the Encyclopaedia of South African Theatre and Performance

- Nancy T. Kearns collection of Athol Fugard materials, 1983-1996, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

The Island is a play written by Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona.

The apartheid-era drama, inspired by a true story, is set in an unnamed prison clearly based on South Africa's notorious Robben Island prison, where Nelson Mandela was held for twenty-seven years. It focuses on two cellmates, one whose successful appeal means that his release draws near and one who must remain in prison for many years to come. They spend their days performing futile physical labor and nights rehearsing in their cell for a performance of Sophocles' Antigone in front of the other prisoners. One takes the part of Antigone, who defies the laws of the state to bury her brother, and the other takes the part of her uncle Creon, who sentences her to die for her crime of conscience. The play draws parallels between Antigone's situation and the situation of black political prisoners. Tensions arise as the performance approaches, especially when one of the prisoners learns that he has won an early release and the men's friendship is tested.

Structure[edit]

The play has four scenes. It opens with a lengthy mimed sequence in which John and Winston, two cell mates imprisoned on Robben Island, shovel sand in the scorching heat, dumping the sand at the feet of the other man, so that the pile of the sand never diminishes. This is designed to exhaust the body and the morale of the prisoners. Later scenes include a play within a play, as Winston and John perform a condensed two-person version of Antigone by Sophocles.

History[edit]

The play was first performed in Cape Town, at a theatre called The Space, in July 1973. In order to evade the draconian censorship in South Africa at the time (plays dealing with prison conditions, etc., were prohibited), the play premiered under the title, Die Hodoshe Span. It was next staged at the Royal Court Theatre in London, with John Kani and Winston Ntshona portraying John and Winston respectively. The Broadway production, presented in repertory with Sizwe Banzi Is Dead, opened on November 24, 1974 at the Edison Theatre, where it ran for 52 performances.

In an unusual move, Kani and Ntshona were named co-Tony Award nominees (and eventual co-winners) for Best Actor in a Play for both The Island and Sizwe Banzi Is Dead.

Over the next thirty years, Kani and Ntshona periodically performed in productions of the play. Notable among them were the Royal National Theatre in 2000 [1], reported at the time as their final production, although they went on to star at the Old Vic in 2002 [2] and the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2004 [3].

Plot[edit]

John and Winston share a prison cell on an unnamed Island. After another day of hard labor and having been forced to run while shackled and then beaten, they return to their cell. They tend each other's wounds, share memories of times at the beach and rehearse for the prisoner-performed concert which is imminent. They are going to perform a scene from an abridged version of Antigone by Sophocles. John will play Creon and Winston will play Antigone.

When he sees himself in his costume, Winston tries to pull out of playing a female role, fearing he will be humiliated. John is called to the governor's office. He returns with news that his appeal was successful and his ten-year sentence has been commuted to three years: he will be free in three months. Winston is happy for him. As they imagine what leaving prison and returning home will be like, Winston begins to unravel. He doubts why he ever made a stand against the regime, why he even exists. Having said it, he experiences a catharsis, and accepts that he must endure.

The final scene is their performance of Antigone. After John-as-Creon sentences Winston-as-Antigone to be walled up in a cave for having defied him and done her duty towards her dead brother, Winston pulls off Antigone's wig and yells 'Gods of Our Fathers! My Land! My Home! Time waits no longer. I go now to my living death, because I honored those things to which honor belongs'. The final image is of John and Winston, chained together once more, running hard as the siren wails.

Characters[edit]

- John has been imprisoned for belonging to a banned organization.

- Winston, we find out later was imprisoned for burning his passbook in front of the police. This was a serious crime, as the passbook was used to segregate and control the South African people.

- Hodoshe, an unseen character: he is referred to and represented by the sound of a prison whistle. He is a symbol of the apartheid state and racist rule. The literal translation for Hodoshe is 'carrion fly' (as mentioned in the play), a large green fly.

Themes[edit]

- Obedience and civil disobedience

- Brotherhood

- Freedom – bodily freedom, freedom of conscience and freedom of the mind

- Memory, imagination, and the transformative power of performance

Language[edit]

Although the play is in English, Afrikaans and Xhosa words are spoken as well.

Broadway awards and nominations[edit]

The Coat By Athol Fugard

- Tony Award for Best Play (co-nominee with Sizwe Banzi)

- Tony Award for Best Actor in Play (Kani and Ntshona, winners)

- Tony Award for Best Direction of a Play (nominee)

- Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Actor in a Play (Kani and Ntshona, co-nominees)

- Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Director of a Play (nominee)

- Drama Desk Award for Outstanding New Foreign Play (co-nominee with Sizwe Banzi)

The Island By Athol Fugard Pdf Free I Love

External links[edit]

The Island Athol Fugard